It was our last evening in Santos, and we were having beers and hamburgers at this great bar. The Bookseller told me that he planned to write a book one day called The Bookseller in the Tropics, but until then he used Facebook to revenge himself on annoying customers. They seem to be just as many in Brazil as in Sweden.

A few examples:

An annoying lady came by the bookshop. I missed the background on why he felt so sure he couldn’t help her, but apparently she wasn’t having it anyway:

She: “I have looked everywhere! You are the only one that can help me!”

The Bookseller: “I doubt it.”

She: “I’m sure you can!”

He: “I’m sure I can’t.”

And so it continued, back and forth, until he decided to just stand there, quiet and immobile, “turning slowly into a stone” until she eventually left.

He also shared with me the best example of the customer that doesn’t know what she’s looking for (you know the type: “I don’t know the title or the author or what the book’s about, but I remember that the cover is red. Or possibly blue. Can you look it up in the computer?”). His customer didn’t even know the colour, but she knew it was “this thick”, using her index finger and thumb to measure it. Naturally the Bookseller then walked around the bookshop measuring all the books he saw. I suspect that she too left in the end.

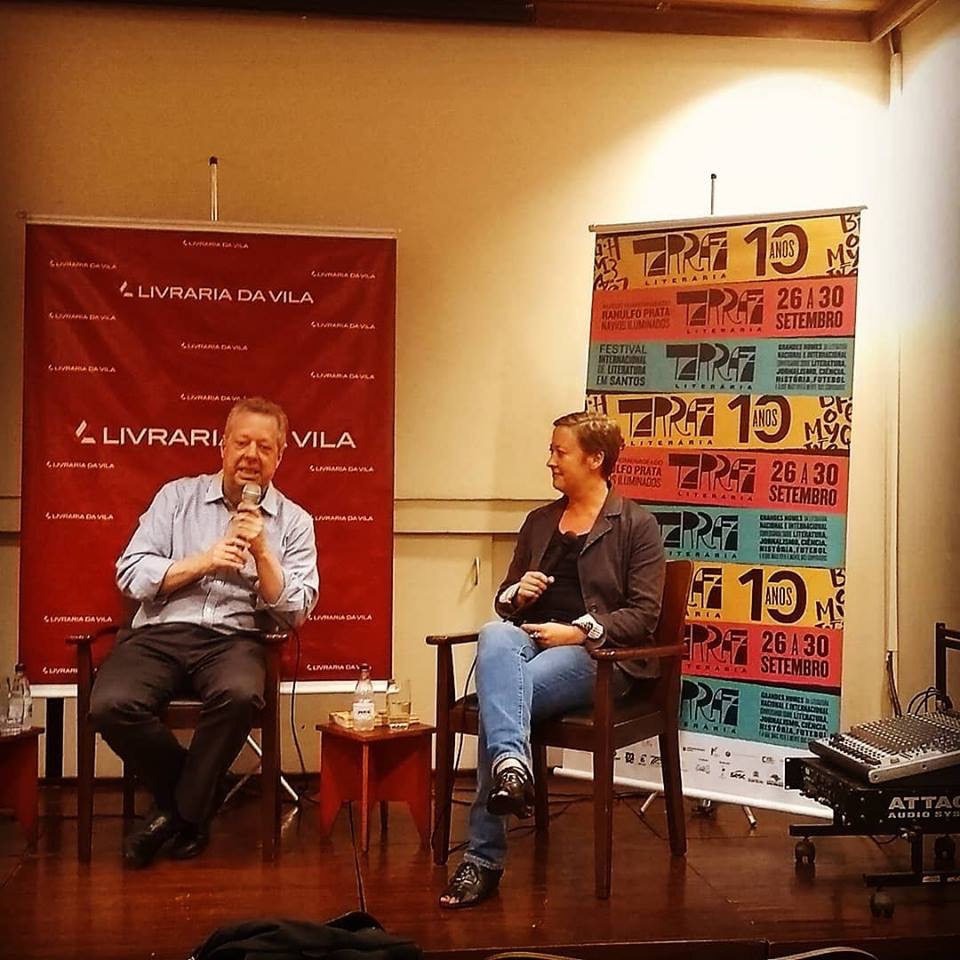

But I don’t want you to think that the Bookseller is asocial or grumpy or dislike people like, say, me. No, no. Wherever he goes someone is calling out a greeting and receiving a smile, a pat on the shoulder in return and a loud and happy “oi!”. He seems to know half the city and like everyone; and everyone certainly likes him.

Speaking of “Oi!”, I have to introduce you to the Driver. You might remember him from the drive from the airport when I had just arrived to this fascinating country. And he continued to drive people back and forth between Sao Paulo and Santos all week. We often see each other outside of the theatre where the book festival is; he while dropping off or picking up or waiting for people, me while smoking. He talks very little English and I almost no Portuguese, but we always greet each other like old friends. “Hello!” he says, and I reply with a “Oi! Todo ben?” He smiles encouragingly everytime and pretends to be impressed by my Portuguese. After that we have basically used all the words we have in common, and have to rely on gestures, smiles and shrugs. But don’t they always say that a true sign of friendship is that you can be quiet together and don’t have to talk all the time?

A new writer had joined us that evening called Antonio Ladeira, a Portuguese writer and literary scholar who lives in Lubbock, Texas. He’s the only one I met who voluntarily moved to Lubbock. He was extremely fond of and knowledgeable about (fountain) pens and could never remember a name. By now he had called Ana Margarida some three or four different things, like Ana Christina, Ana Maria etc. I like pens as much as the next author, but I’m not even close his level. He kindly informed me that there were several great pen shows in the US (he had been to them too, I’m sure). He had brought three pens to Brazil: one “cheaper, from China” that he didn’t really care about (I didn’t either). The second one was a Parker ’51, which apparently is an iconic pen that was produced between the 30ies and 70ies (or something like it), but still retains a classic, modern feel some four decades after it stopped being produced. I loved that pen and will definitely buy one. I don’t remember the name of the third one, but it was the most expensive, and it was also the pen that Neil Gaiman swore by. He kindly let me try all of them, and then he turned to me and said: “So, Margaret…”He blinked confusedly when me and Ana Margarida started laughing. “Now you remember Margaret”, she said and shook her head.

At the end of the evening I turned to the Bookseller and told him that he really should write that novel. “But maybe you shouldn’t have told me about it, because it’s such a great title that I might steal it.” – “It’s my gift to you”, he replied seriously and then added: “Since you’re stealing it anyway, I’m gifting it to you.”

PS. I was kidding. I would never steal someone elses title. But I would love to read that book.