I have arrived in Brazil, and already found myself in the middle of a movie. It’s just not clear yet exactly which movie it is.

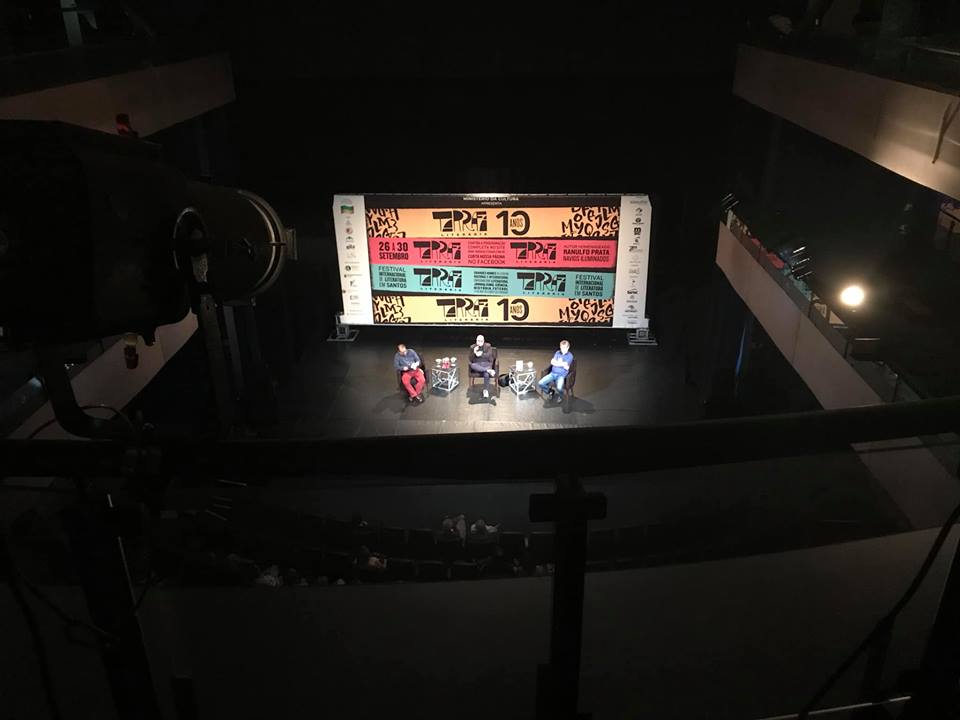

My first impression was very much Lost in translation. I am at a bookfair in Santos, outside of Sao Paulo, and have very little idea about exactly what I’m supposed to do here. My guide explained my schedule to me in the car from the airport, but the only thing I’m sure about is that he is going to pick me up every day for lunch at 1 pm and dinner at 7. I have a flyer where my name is mentioned, but it is of course all in Portugese.

I was groggy from lack of sleep and an even more serious lack of nicotine and found myself nodding at everything while highrisers of Sao Paolo passed by outside of the car window (all of them in different version of sand colour, beige or white) with favelas in between. Our uber driver added his part to this guided tour and my guide translated enthusiastically. “That grass belongs to the university of Sao Paolo, you know X? The football player? He has an apartment in that building. He has several other apartments as well, of course. Sao Paolo is the city in the world with the largest amount of helicopters. Also the city that uses uber most. That’s a pet store. It’s a very big industry in Brazil.” Our uber driver himself had 3 or 4 or possibly 34 dogs. It was a bit unclear. When we left Sao Paolo behind we was caught in a more literal fog: Santos is built in a valley, surrounded by tree covered mountains, and those mountains are almost always shrouded in fog. It was all very beautiful. The road goes so stubbornly downwards that our ears were blocked. My guide asked if I knew how to get rid of it, and I assured himl that I did. Also, I was yawning, so that took care of it.

And yet, my experience is very different from Lost in translation, and I don’t just mean the lamentable lack of Bill Murray or Scarlett Johansson at the hotel bar (trust me, I’ve looked). No, the difference is all in my eminent and very enthusiastic guide and translator. It shall be my mission today to take a photograph of him, since he will be my best friend in the coming week.

Ivander found me at the airport, or if I found him, and greeted me with a so enthusiastic “Hallå! God dag!” that I blinked confusedly at him and answered in Swedish. Apparently he had looked up how to say “Good evening” in Swedish earlier and had a bit of a crisis when it turned out that he was meeting me instead in the morning. But he rose to the occasion and learn “good morning” as well. Ivander had also googled me, read my blog and in general done all the neccessary research, so the first thing he said after “god dag” was: “Cigarette?” I felt a deep and immediate connection with him.

“I am going to be with you all the time!” he said happily, but then added conscientiously: “While at the same time respecting your Swedish space.” Ivander was convinced we were in a quite different movie: “I am going to be Andrea, and you Miranda!” I looked down on the clothes I’d traveled and slept in for the last sixteen hours and felt that nothing was more unlikely than me turning into either Meryl Streep or Anna Wintour.

The car ride to Santos to about three hours, and he used the time to teach me to say hi, how are you and thank you in portugese; discuss European royalty (“Do you know your queen is Brazilian?” he said. “I love her!” Although his real favourite was the Danish royal family, he found queen Margrethe “so cute!”) and play Eurovision songs for me. His research had led him to believe that I was not a huge fan, but we still both happily sang along together to Måns Zelmerlöws Heroes while the high risers of Sao Paolo passed by outside.

I also managed to negotiate a free first evening (the schedule of course said for him to pick me up for dinner at 7 pm). For a long time it seemed uncertain how it would go, since I mumbled something vague about being tired and he unfortunately thought I implied that he might tire of me. “No, no! I could never tire of you!” he immediately assured me.

I don’t want you to worry that I am suddenly going to become all demanding and unreasonable. He has already taken me to a bookstore, so a, I don’t know what other demans I could possibly make, and b, he took me to a bookstore, which as we all know is the beginning of a beautiful friendship. I will return later with a report on Santos.